Quick Answer: Bread rises primarily due to yeast fermentation, which produces carbon dioxide gas that gets trapped in the dough’s elastic gluten network. This biological and chemical process is influenced by ingredients, temperature, and time, collectively transforming a dense mixture into the light, airy bread we enjoy.

The Role of Yeast in Bread Rising

At the heart of bread’s magical transformation from a dense dough to a fluffy loaf is a remarkable microorganism: yeast. These tiny single-celled fungi are the powerhouse behind the bread fermentation process that makes your favorite sandwich possible.

When activated in dough, yeast cells begin their important work:

- They consume sugars present in flour through a process called fermentation

- As they metabolize these sugars, they produce carbon dioxide gas as a byproduct

- This CO₂ creates bubbles within the dough, causing it to expand

- Simultaneously, yeast produces ethanol and organic acids that contribute to bread’s distinctive flavor profile

The biology of bread is fascinating – yeast doesn’t just make bread rise; it’s responsible for much of the flavor development. During fermentation, yeast produces over 500 compounds that contribute to the aroma, taste, and texture that make freshly baked bread so irresistible.

How Yeast Fermentation Works

Yeast fermentation follows two distinct pathways depending on oxygen availability:

- Initial aerobic phase: With oxygen present, yeast respires and produces CO₂ and water

- Anaerobic fermentation: As oxygen depletes, yeast switches to producing CO₂ and ethanol

This continuous gas production is what gives bread its rise, with each tiny bubble contributing to the bread’s volume and texture. The longer the fermentation, the more complex the flavor development becomes – which is why many artisan bakers prefer slow-rise methods.

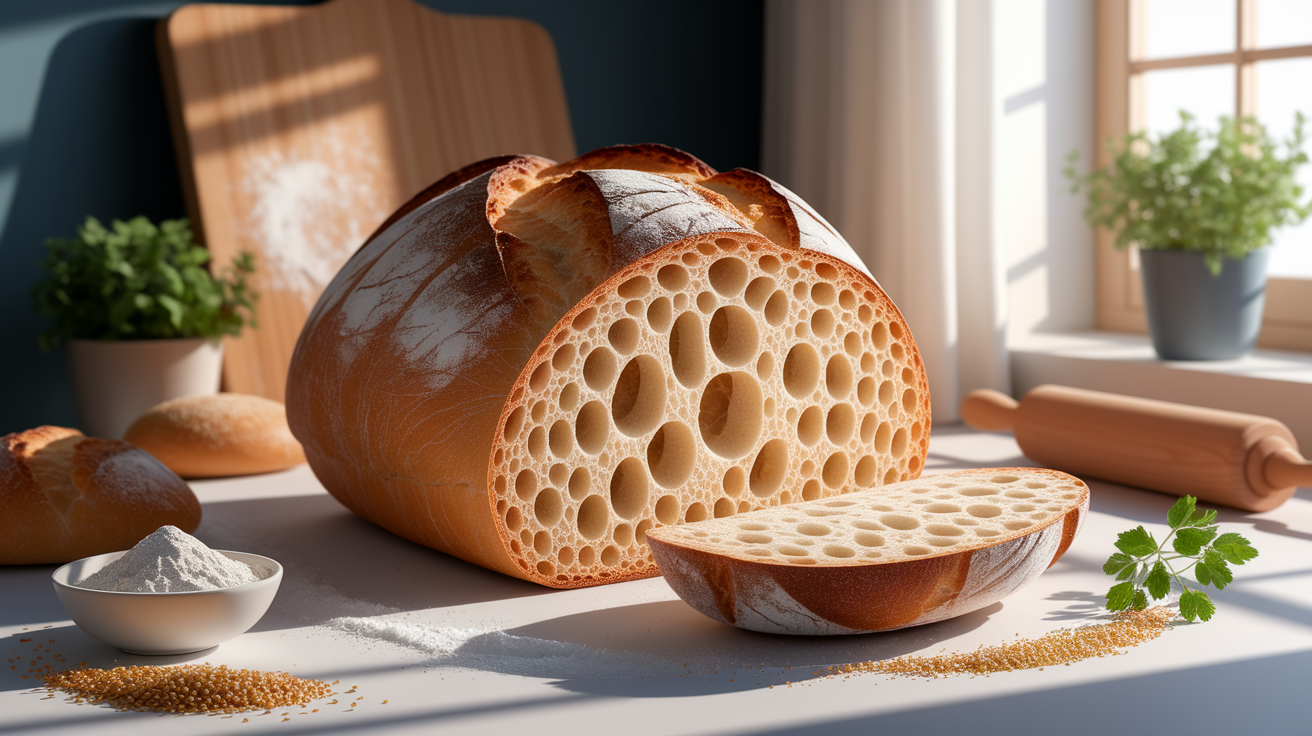

The Gluten Network: Bread’s Structural Backbone

While yeast provides the “lift,” gluten provides the structure. Without this remarkable protein network, the gas produced during fermentation would simply escape, leaving you with flat bread. The science behind the risen loaf involves this critical relationship between gas production and gas retention.

When flour meets water, something remarkable happens:

- Two wheat proteins, glutenin and gliadin, hydrate and bond together

- These proteins form long, interconnected strands of gluten

- Kneading aligns these strands and strengthens their connections

- The resulting elastic network can stretch like a balloon when filled with CO₂

Gluten development is why bakers knead dough so thoroughly – they’re not just mixing; they’re developing the dough’s strength and elasticity. This gluten network acts like millions of tiny balloons that capture the carbon dioxide produced by yeast, allowing the dough to rise instead of letting the gas escape.

The Importance of Flour Selection

Not all flours are created equal when it comes to gluten formation:

- High-protein bread flour: Contains 12-14% protein, ideal for creating strong gluten networks in yeast breads

- All-purpose flour: Contains moderate protein (9-11%), suitable for many bread types

- Pastry/cake flour: Low in protein (8-9%), creating less gluten for tender baked goods

The flour protein content directly affects how well your bread will rise. Bread flour’s higher protein content creates a stronger gluten structure that can better trap gas bubbles, resulting in higher rising bread with an open crumb structure.

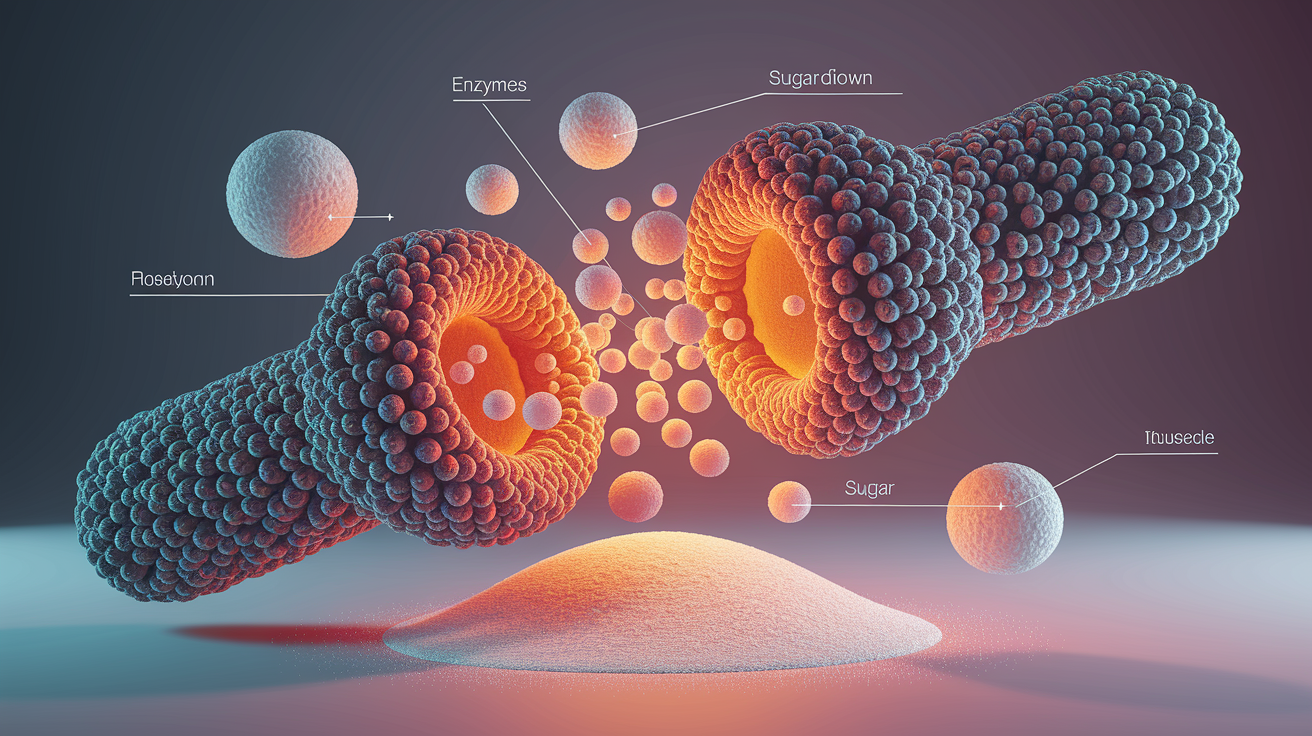

Enzymatic Action and Sugar Breakdown

While yeast and gluten get most of the attention, enzymes play a crucial behind-the-scenes role in bread rising. These biological catalysts, naturally present in flour, are essential for providing yeast with an ongoing food supply.

The most important enzymatic reactions include:

- Amylase activity: These enzymes break down complex starches in flour into simple sugars

- Sugar production: The resulting maltose and glucose become readily available food for hungry yeast cells

- Continuous fuel supply: This ongoing sugar breakdown ensures fermentation continues throughout the rising process

This biochemical interplay creates a self-sustaining system where enzymatic starch degradation provides a steady stream of sugars for yeast fermentation. Without these enzymes, yeast would quickly consume the available sugars and fermentation would halt, resulting in under-risen bread.

Dough Hydration and Enzyme Function

Proper dough hydration is critical for optimal enzyme function:

- Water activates enzymes in flour

- Higher hydration doughs often facilitate more enzyme activity

- This increased activity can lead to more sugar availability for yeast

- The result is often more vigorous fermentation and better rise

Many professional bakers manipulate dough hydration precisely to control enzymatic activity and fermentation rates, balancing rise time with flavor development.

Temperature’s Impact on Fermentation

If yeast is the engine of bread rising, temperature is the accelerator pedal. The relationship between temperature and yeast activity is one of the most crucial factors affecting how quickly and effectively bread rises.

Temperature affects yeast fermentation in several ways:

- Cold temperatures (below 68°F/20°C): Slow yeast activity, resulting in longer rise times but often more complex flavors

- Room temperature (68-72°F/20-22°C): Moderate activity, providing a good balance of rise time and flavor development

- Warm temperatures (80-90°F/27-32°C): Accelerated fermentation and faster rise

- Hot temperatures (above 95°F/35°C): Risk of yeast stress or death, potentially killing the rise

During baking, a phenomenon called “oven spring” occurs when the dough experiences a final burst of rising. The heat causes gases to expand and yeast to have a final fermentation surge before the high temperatures kill the yeast cells and set the bread structure.

Managing Temperature for Perfect Rise

Professional bakers carefully control dough temperature because it so dramatically affects fermentation:

- They adjust water temperature based on ambient conditions

- Many use proofing chambers or boxes with precise temperature control

- Some recipes call for refrigerated fermentation (“cold proofing”) to develop flavor

Understanding how temperature affects dough helps explain why bread may rise differently in winter versus summer, and why consistent temperature control is one of the secrets to consistently good bread.

Different Yeasts, Different Results

Not all yeasts are created equal, and the type you choose can significantly impact how your bread rises. The variety of leavening agents available to bakers each bring their own characteristics to the bread-making process.

Common types of yeast include:

- Active Dry Yeast: Requires proofing in warm water to activate before use

- Instant Yeast: Can be added directly to dry ingredients without proofing

- Fresh/Compressed Yeast: Highly perishable but prized by professional bakers for its performance

- Sourdough Starter: Contains wild yeasts and bacteria that work together to leaven bread while developing unique flavors

Each of these yeast varieties affects fermentation differently. Commercial yeasts typically produce rapid, predictable rises, while sourdough fermentation is slower and produces more complex flavors along with natural preservatives that extend shelf life.

Chemical Leavening Alternatives

Not all bread rising relies on yeast. Some quick breads use chemical leavening agents:

- Baking soda: Reacts with acids to release carbon dioxide immediately

- Baking powder: Contains both acid and base components for controlled CO₂ release

- Steam: In breads like puff pastry and croissants, water converts to steam during baking, creating rise

While these methods produce CO₂ through different mechanisms than yeast fermentation, the principle remains the same: gas expansion creates rise.

Conclusion: The Art and Science of Bread Rising

The science behind bread rising represents a beautiful intersection of biology, chemistry, and physics. From the microscopic activity of yeast cells to the elastic properties of gluten proteins, each element plays a crucial role in transforming simple ingredients into one of humanity’s most foundational foods.

The next time you bite into a slice of bread, remember the incredible science at work:

- Yeast fermentation producing the gas that creates rise

- Gluten networks trapping that gas in countless tiny bubbles

- Enzymes ensuring a steady food supply for yeast activity

- Temperature controlling the rate of these biological processes

Understanding these principles doesn’t just satisfy scientific curiosity—it empowers you to become a better baker, troubleshoot problems with bread recipes, and appreciate the remarkable complexity behind something as seemingly simple as a rising loaf of bread.