Quick Answer: Ice can vanish without melting through a process called sublimation, where it transforms directly from solid to vapor. Under certain conditions, small ice particles can actually sublimate at rates comparable to liquid water evaporation due to similar vapor diffusion mechanics in the surrounding air.

Introduction – The Curious Case of Vanishing Ice

Have you ever returned to your freezer to find ice cubes that have mysteriously shrunk? Or noticed how a snowbank can gradually disappear even when temperatures remain below freezing? These aren’t cases of magical disappearance but rather examples of a fascinating scientific process at work.

Ice seems permanent in cold environments, yet it can vanish right before our eyes without ever becoming liquid. This phenomenon puzzles many people who assume ice must always melt before evaporating. The reality is much more interesting—ice has a secret pathway to transform directly from solid to gas, bypassing the liquid phase entirely.

This invisible transformation explains many everyday mysteries, from shrinking ice cubes to disappearing snow on cold, dry days. Let’s explore the science behind this remarkable process and discover why ice sometimes evaporates faster than you might expect.

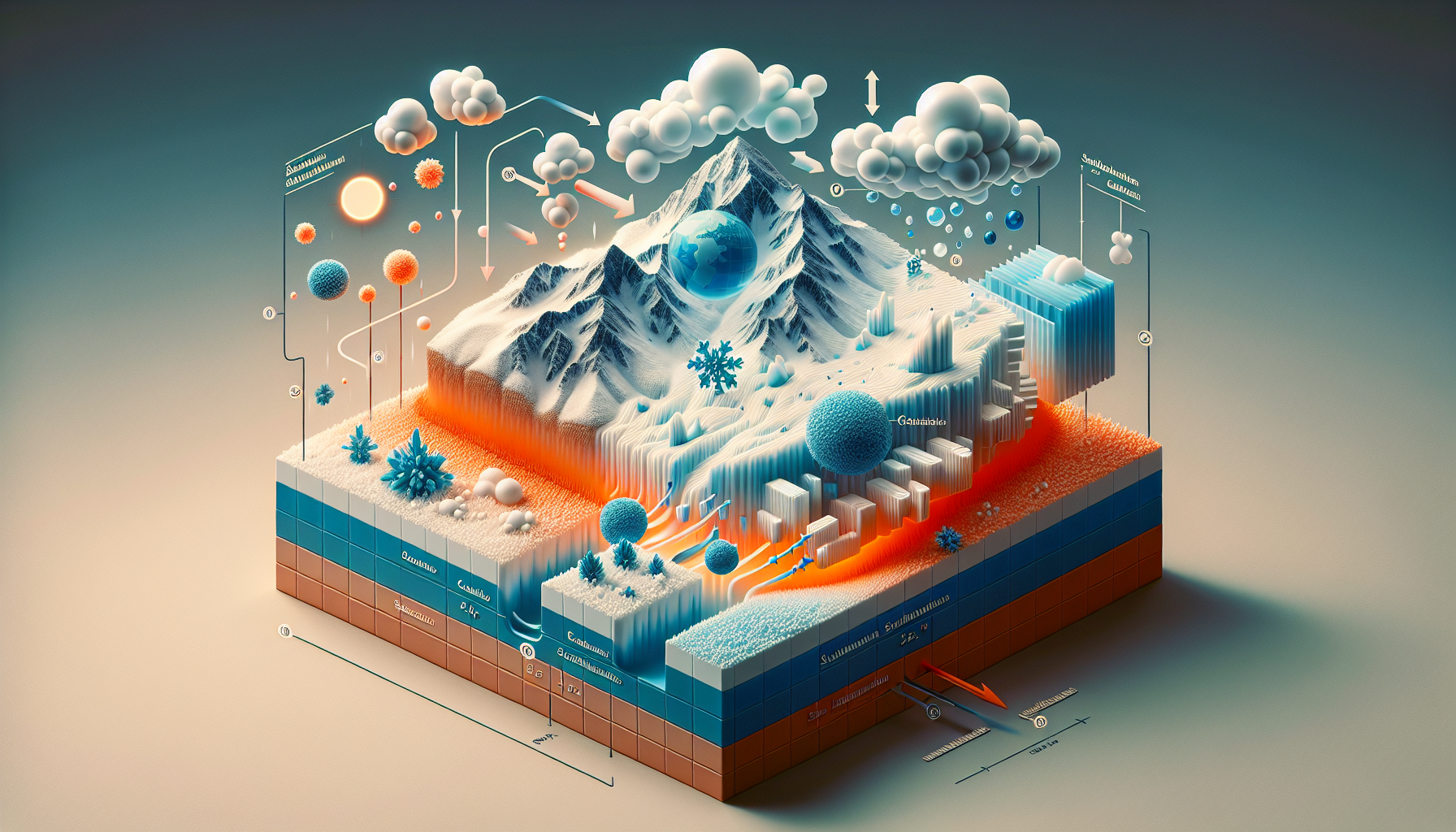

The Science Behind Sublimation

Sublimation is the direct transition of a substance from solid to gas without passing through the liquid state. While we typically expect ice to melt into water before evaporating, under the right conditions, water molecules can break free from the crystal structure of ice and escape directly into the air as water vapor.

At the molecular level, here’s what happens:

- Ice is made of water molecules arranged in a rigid crystal lattice

- These molecules are constantly vibrating, even at very low temperatures

- Some molecules at the surface gain enough energy to break free from the bonds holding them to other molecules

- Instead of forming liquid water, these energetic molecules escape directly into the air as water vapor

Contrary to what intuition might suggest, research from the University of Amsterdam revealed something remarkable: small ice particles can sublimate at rates comparable to the evaporation of similarly sized liquid water droplets! This challenges our assumption that liquids always evaporate faster than solids.

The key insight is that both processes—sublimation of ice and evaporation of water—are primarily limited by how quickly water vapor can diffuse away from the surface through the surrounding air, rather than by the phase change itself.

The Thermodynamics at Play

From a thermodynamic perspective, sublimation occurs when the vapor pressure of ice exceeds the partial pressure of water vapor in the surrounding air. At 0°C, ice has a vapor pressure of about 611 Pascals—meaning water molecules are constantly attempting to escape into the air.

When we compare sublimation to the more familiar melting-then-evaporating pathway:

- Sublimation requires more energy in a single step (about 2,834 kJ/kg)

- The two-step process of melting then evaporating requires similar total energy

- However, sublimation allows for mass transfer even at temperatures where liquid water cannot exist

Factors Influencing Sublimation Rates

Several environmental and physical factors determine how quickly ice sublimates. Understanding these can explain why ice sometimes seems to disappear so rapidly.

Humidity Levels

Perhaps the most significant factor is relative humidity. In dry air, the sublimation rate increases dramatically:

- Low humidity creates a steep concentration gradient that pulls water molecules away from ice

- In very dry conditions, like those in freezers or high-altitude environments, sublimation accelerates

- High humidity slows sublimation as the air becomes more saturated with water vapor

This explains why ice cubes shrink faster in frost-free freezers, which actively remove humidity from the air.

Air Movement

Air circulation plays a crucial role in sublimation rates, as noted by the National Weather Service:

- Still air allows water vapor to accumulate near the ice surface, slowing further sublimation

- Moving air continuously sweeps away water vapor, maintaining the concentration gradient

- Windy conditions can dramatically increase sublimation rates, even at very low temperatures

Surface Area to Volume Ratio

The shape and size of ice significantly affect sublimation rates:

- Small ice particles and snowflakes with high surface area-to-volume ratios sublimate much faster

- Large ice blocks sublimate more slowly relative to their mass

- This explains why powdery snow can disappear quickly while larger ice formations persist longer

The National Snow and Ice Data Center notes that this principle explains why fresh, fluffy snow with intricate crystal structures undergoes rapid transformation, with sharp edges becoming rounded through preferential sublimation.

Temperature Effects

While sublimation occurs even at extremely low temperatures, the rate increases with temperature:

- Higher temperatures provide more energy for water molecules to break free from ice

- The vapor pressure of ice increases with temperature, accelerating sublimation

- Just below freezing (around -5°C to 0°C) often shows notably high sublimation rates

Practical Implications of Sublimation

Understanding sublimation explains many common observations and has important applications in both daily life and industry.

Everyday Observations

Several common phenomena result from ice sublimation:

- Freezer burn: The dry, discolored patches on frozen food occur when ice crystals in the food sublimate, leaving behind dehydrated areas

- Shrinking ice cubes: Ice cubes that get smaller in your freezer without melting are undergoing sublimation

- Disappearing snow: Snow that vanishes on cold, dry days without leaving wet spots is sublimating directly to vapor

- Changing snow texture: Skiers notice that fresh, powdery snow gradually becomes more compact and rounded due to sublimation effects

The rapid disappearance of snow in dry climates often puzzles people who expect to see puddles forming. Instead, the snow simply vanishes into the air.

Industrial and Scientific Applications

The sublimation process has been harnessed for various practical applications:

- Freeze-drying: Food preservation and pharmaceutical production use controlled sublimation to remove water without damaging the product’s structure

- Weather forecasting: Meteorologists account for sublimation when predicting snow accumulation and melt rates

- Laboratory techniques: Scientists use sublimation for purification and crystallization processes

You can even observe sublimation at home with a simple demonstration experiment using dry ice or regular ice under the right conditions.

Related Scientific Curiosities

Sublimation connects to other interesting scientific phenomena, including the puzzling Mpemba effect—where hot water sometimes freezes faster than cold water. While not directly about ice evaporation, this effect involves similar principles of molecular behavior and phase transitions.

The comparison between sublimation and evaporation rates also challenges our intuitive understanding of phase transitions, demonstrating that what seems obvious isn’t always scientifically accurate.

Conclusion – The Invisible Transformation

Ice sublimation represents one of nature’s more subtle but fascinating processes—a direct pathway between solid and gas that operates silently around us. The next time you notice ice cubes shrinking in your freezer or snow disappearing on a cold day, you’re witnessing this remarkable phase transition in action.

The surprising discovery that small ice particles can sublimate just as quickly as water droplets evaporate reminds us that scientific reality often defies our everyday intuition. It’s a perfect example of how understanding the molecular world can explain the curious phenomena we observe in our daily lives.

From frozen foods to winter landscapes, sublimation shapes our world in ways both practical and beautiful—an invisible transformation that connects the ordinary to the extraordinary through the elegant principles of physics and chemistry.