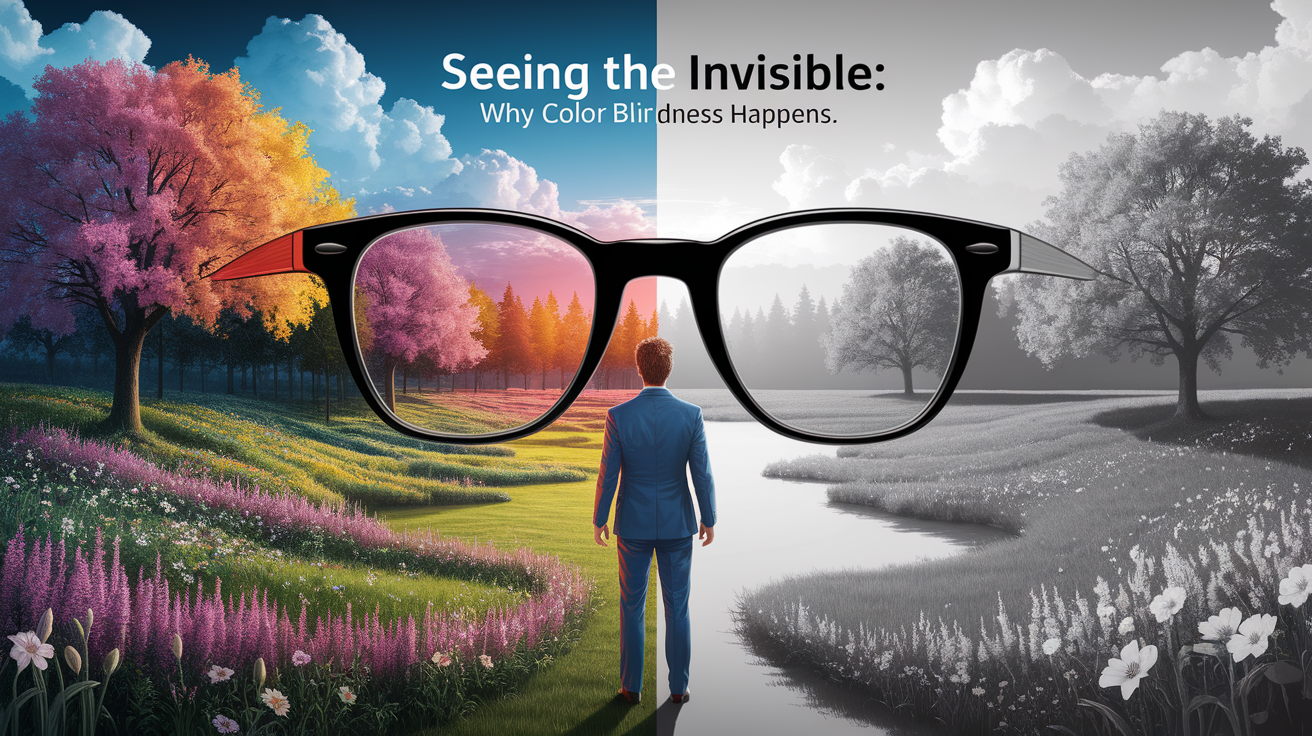

Quick Answer: Color blindness happens when the light-sensing cone cells in your eyes can’t detect certain wavelengths of light correctly, making it hard to tell some colors apart. This can be inherited through genes or caused later in life by illness, injury, or aging changes in the eyes.

Seeing the Invisible: Why Color Blindness Happens

Color vision works a lot like a sophisticated camera sensor. In our eyes, three types of cone cells in the retina each detect different ranges of light wavelengths — short (blue), medium (green), and long (red). These cells contain special photopigments that absorb light and send signals to the brain, which blends them into the colors we see.

When these photopigments are missing, faulty, or damaged, your brain doesn’t get the full color picture. This results in a color vision deficiency, which ranges from trouble telling reds and greens apart to seeing the world only in shades of gray.

Depending on the cause, color blindness can be present from birth (congenital) or develop later in life (acquired).

Genetic Causes of Color Blindness

The most common reason for color blindness is an inherited genetic difference affecting opsin proteins in cone cells. These proteins determine each cone’s spectral sensitivity—which wavelengths it absorbs best. When a genetic mutation alters or removes an opsin protein, the corresponding cone type can’t properly detect its target color.

- Red-Green Color Blindness – This is the most common inherited condition and includes:

- Protanopia – Missing or defective red cone photopigments.

- Deuteranopia – Missing or defective green cone photopigments.

- Blue-Yellow Color Blindness – Known as tritanopia, caused by problems in blue cone function (less common).

These conditions often follow an X-linked recessive inheritance pattern. Because the gene is on the X chromosome, males (with only one X chromosome) are more likely to have red-green color blindness, while females usually need two affected X chromosomes to experience it.

Inherited forms are usually stable and lifelong. If you’re born with it, your color vision deficiency doesn’t usually worsen over time.

Acquired Causes: When Life Alters Your Colors

Not every case of color blindness is genetic. Sometimes, the eye’s “hardware” or the brain’s “software” gets damaged along the way. This can happen due to medical conditions, injury, or chemical effects.

According to the National Eye Institute, acquired causes include:

- Diseases – Diabetes, glaucoma, macular degeneration, Alzheimer’s disease, and multiple sclerosis can damage the retina or optic nerve.

- Injury – Trauma to the eye or brain regions that process color.

- Chemicals – Exposure to certain chemicals like carbon disulfide or fertilizers may impair cone cells.

- Medications – Some, like hydroxychloroquine, can affect the retina’s photoreceptors.

Acquired color blindness might affect just one eye, may change over time, and in some cases, can be improved if the cause is treated.

Aging and Your Color Perception

As we get older, our eyes go through natural wear and tear. This can subtly (or not so subtly) influence how we see colors.

Common age-related factors include:

- Cataracts – Cloudy lenses scatter light, making colors look faded or yellowed.

- Macular Degeneration & Glaucoma – Damage the retina and optic nerve, reducing color discrimination.

- Blue-Yellow Deficiency – More common with age-related changes than red-green loss.

The Mayo Clinic notes that these changes can slowly progress, so people may not notice color differences until they compare with younger eyes or have cataracts removed.

Palette of Perspective: Final Thoughts on Why Color Blindness Happens

Whether inherited at birth through your genes or acquired later in life through illness, injury, or aging, color blindness all comes down to the same basic principle: something is preventing your cone cells from delivering accurate wavelength information to your brain. Without precise input, your mind paints a slightly different picture of the world.

Understanding why color blindness happens can help with early testing, safety planning (like adjusting color-coded materials), and even appreciation for how diverse human vision can be. While the world might not look exactly the same to everyone, it’s still full of fascinating details and beauty—just seen through different palettes.