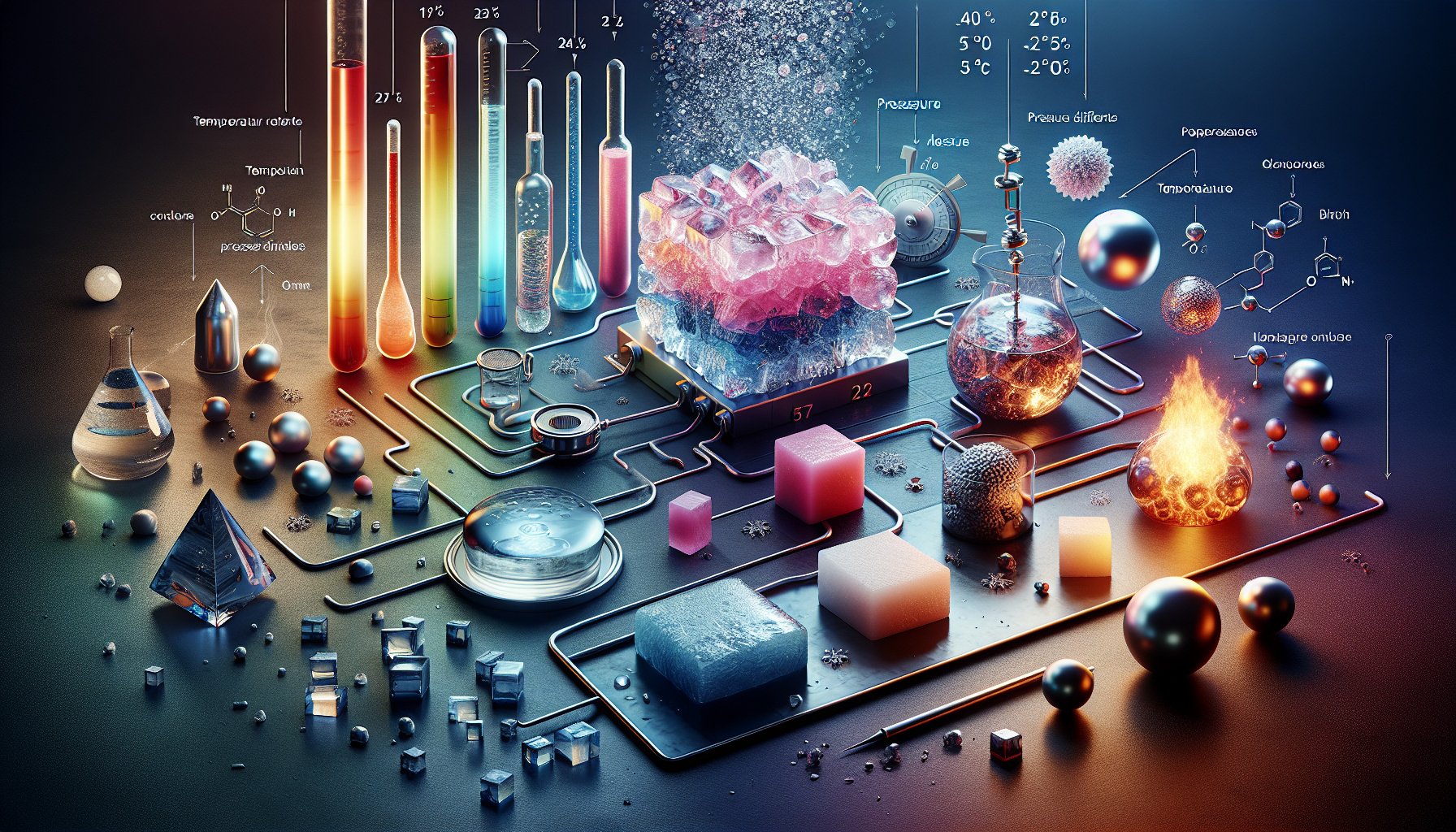

Quick Answer: When heat meets ice, it first raises the temperature of the frozen water until reaching 0°C (32°F), at which point additional heat energy breaks the hydrogen bonds in ice’s crystalline structure without raising temperature further. This process, requiring 79.8 calories per gram of latent heat, transforms solid ice into liquid water while maintaining the same temperature throughout the phase change.

The Immediate Impact of Heat on Ice

When heat first encounters ice, it doesn’t immediately cause melting. Instead, it increases the temperature of the ice itself. Ice has a specific heat capacity of approximately 0.50 cal/g·°C, which means it requires this amount of heat energy to raise the temperature of one gram of ice by one degree Celsius.

What’s happening at the molecular level? As ice absorbs thermal energy:

- The molecules in the ice begin to vibrate more intensely

- The rigid crystal structure starts to weaken as hydrogen bonds between water molecules become less stable

- The temperature of the ice gradually increases toward the melting point

Interestingly, as ice approaches its melting point, its heat capacity actually increases slightly. This happens because the molecular vibrations intensify as the hydrogen bonds begin to weaken, requiring more energy to continue raising the temperature. You can visualize this process as molecules jiggling more frantically within their positions in the ice’s crystalline lattice.

The Melting Point: Where Heat Meets Ice

When ice reaches 0°C (32°F), something remarkable happens. Additional heat no longer raises the temperature of the ice. Instead, this energy is used entirely for the phase change from solid to liquid.

This transformation requires significant energy called the latent heat of fusion. For ice, this value is 79.8 cal/g – nearly 160 times more energy than what’s needed to raise the same amount of ice by just one degree! This explains why ice melts relatively slowly even in warm environments.

During this phase change:

- Heat energy breaks the hydrogen bonds that hold water molecules in their rigid crystalline arrangement

- The temperature remains constant at 0°C despite continuous heat addition

- Molecules gain enough energy to move freely as liquid water

- The orderly structure of ice collapses into the more fluid arrangement of liquid water

This process creates what scientists call a temperature plateau – a period where temperature remains constant despite ongoing heat addition. Only after all the ice has completely melted will the temperature begin rising again, now at water’s higher specific heat capacity of 1.00 cal/g·°C.

Heat Transfer Mechanisms

Heat can reach and affect ice through three primary mechanisms:

- Conduction: Direct transfer of heat through physical contact

- Convection: Transfer of heat through the movement of liquids or gases

- Radiation: Transfer of heat through electromagnetic waves

The medium surrounding ice dramatically affects how quickly it melts. Ice typically melts faster in water than in air under similar temperature conditions. Why? Water has:

- Higher molecular density (more molecules contacting the ice)

- Greater thermal conductivity

- More efficient heat transfer capability

In air, convection drives the melting process as warmer air rises and cooler air near the ice sinks. However, evaporation of the meltwater can actually slow the process by absorbing additional heat.

When ice is placed in water, the process accelerates significantly. The greater number of water molecules surrounding the ice transfers heat more efficiently, causing faster melting. This is why an ice cube melts much more quickly in a glass of water than when sitting on a plate in the same room.

Factors Influencing Melting Rate

Several factors determine how quickly ice transitions from solid to liquid:

Temperature Differential

The greater the difference between the ice’s temperature and the surrounding environment, the faster heat transfers to the ice. A piece of ice at -20°C will take longer to melt than one already at -1°C in the same warm room.

Salt and Other Impurities

Salt disrupts the equilibrium between ice and water by interfering with hydrogen bond formation. When salt contacts ice, it causes localized melting, absorbing heat from the surroundings and actually dropping the solution temperature. This is why salt is used to melt ice on roads in winter, as it can lower the freezing point well below 0°C.

Humidity

Humidity levels significantly impact melting rates in air. In high humidity, water vapor can condense on the cold ice surface, releasing heat and accelerating melting. In low humidity, evaporation of meltwater absorbs heat, slowing the melting process.

Size and Shape

Ice with greater surface area relative to its volume melts faster. Crushed ice melts more quickly than a single large cube of the same mass because more surface area is exposed to heat.

Insulation Effects

Thicker ice insulates against heat transfer. In natural ice formations, thickness plays a crucial role in determining melting rates, with thicker sections slowing the transfer of heat to the interior ice.

Ice in Natural Environments

In nature, the interaction between heat and ice creates fascinating phenomena and important climate processes.

Sea Ice Dynamics

In oceans, warmer upwelling water melts sea ice through sensible heat transfer, sometimes creating ice-free areas called polynyas. Sea ice effectively reflects solar radiation (high albedo), which initially delays melting until sufficient heat accumulates in the surroundings.

This creates an important feedback mechanism: as sea ice melts, more dark ocean water is exposed, absorbing rather than reflecting sunlight, which warms the water and accelerates further melting.

Insulation Properties

Ice acts as a remarkable insulator, limiting heat exchange between ocean and atmosphere. Thicker ice effectively halts additional ice growth by blocking conductive heat loss from the warmer water below to the colder air above.

In winter conditions, thin ice allows rapid heat loss from ocean to atmosphere, causing faster ice growth, while thick ice slows this process significantly. This self-regulating mechanism helps maintain relatively stable ice thickness in natural conditions.

Conclusion: The Dance of Heat and Ice

The relationship between heat and ice represents one of nature’s most elegant thermodynamic balancing acts. From the first application of heat to frozen water, through the temperature-stable phase change at 0°C, to the complete transformation into liquid, the process follows precise physical principles while creating the conditions that make our planet habitable.

Understanding this relationship helps explain everything from why ice cubes chill our drinks (by absorbing significant heat during melting) to the complex dynamics of Earth’s polar regions. The next time you watch an ice cube melt in your glass, remember you’re witnessing a remarkable energy transformation that follows the same principles whether occurring in your kitchen or across vast polar ice sheets.