Quick Answer

Your body maintains its core temperature at approximately 37°C (98.6°F) through a remarkable system called thermoregulation. This process involves temperature sensors throughout your body, the brain’s hypothalamus acting as a central thermostat, and various physiological responses that generate or dissipate heat as needed to maintain optimal functioning.

Introduction: The Heat is On

Imagine your body as a high-precision machine with thousands of components—enzymes, proteins, and cellular systems—all working best within a surprisingly narrow temperature range. Unlike the outdoor thermometer that might swing from freezing to sweltering, your internal temperature varies by only about 1°C throughout the day.

This remarkable stability isn’t a coincidence. Your body employs an intricate thermoregulation system—a biological thermostat that constantly works to balance heat production and heat loss. This homeostatic mechanism is fundamental to your survival and optimal functioning, affecting everything from your metabolism to your immune system.

But how exactly does your body maintain this delicate balance in environments ranging from freezing mountaintops to scorching deserts? Let’s explore the fascinating science behind your internal temperature control system.

The Central Control: Hypothalamus and Thermoregulation

At the core of your body’s temperature regulation system sits a small but mighty structure—the hypothalamus. Located deep within your brain, this almond-sized region functions as your body’s thermostat, continuously monitoring and adjusting your temperature.

The hypothalamus receives temperature information from two main sources:

- Peripheral thermoreceptors: Located in your skin, these sensors detect environmental temperature changes and send early warning signals before your core temperature is affected.

- Central thermoreceptors: Found in your spinal cord, internal organs, and the hypothalamus itself, these monitor your core body temperature more directly.

The preoptic area (POA) of the anterior hypothalamus serves as the integration center for all this temperature data. When it detects your temperature drifting away from the ideal range, it coordinates responses through your nervous system, particularly the autonomic nervous system, to restore balance.

Think of the hypothalamus as the supervisor in a climate control center, receiving updates from sensors throughout the building (your body) and making adjustments to the heating and cooling systems accordingly.

Mechanisms of Heat Exchange

Your body exchanges heat with its environment through four fundamental physical processes. Understanding these helps explain how your body maintains its ideal temperature in various conditions.

Conduction

Conduction involves the direct transfer of heat between your body and objects in physical contact with it. When you sit on a cold metal bench, heat flows from your warm body to the cooler bench. Conversely, sitting in a hot sauna transfers heat from the bench to your body.

Convection

Convection occurs when air or liquid moves across your skin, carrying heat away. This is why a fan cools you down even when it’s blowing room-temperature air—it increases convective heat loss by disrupting the warm air layer around your skin.

Radiation

Your body continuously emits infrared radiation. On a cold day, more heat radiates from your warm body to the cooler environment. Likewise, standing in direct sunlight means your body absorbs radiation, gaining heat from the sun.

Evaporation

When liquid on your skin converts to vapor, it takes heat energy with it. This is why sweating cools you down—as sweat evaporates, it removes heat from your skin surface. Evaporation is your body’s most powerful cooling mechanism in hot environments.

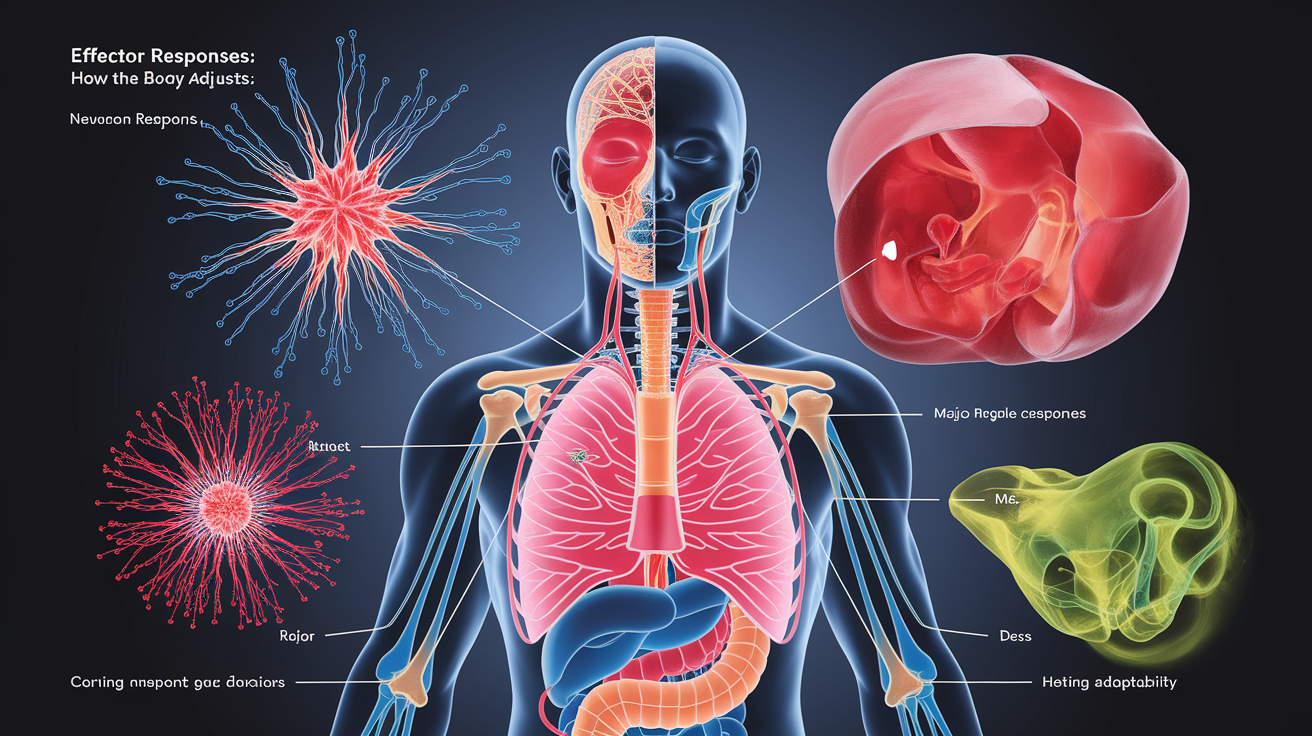

Effector Responses: How the Body Adjusts

When your hypothalamus detects temperature changes, it triggers specific physiological responses designed to either generate heat or dissipate it.

Cooling Down: Responses to Heat

- Vasodilation: Blood vessels near your skin surface widen, increasing blood flow and allowing more heat to radiate away from your body. This is why your skin often appears flushed when you’re hot.

- Sweating: Your body activates millions of eccrine sweat glands, releasing a water-based fluid onto your skin surface. As this sweat evaporates, it cools your skin and the blood flowing just beneath it.

- Reduced Metabolic Rate: Your body may slightly decrease its metabolic activity to generate less heat internally.

Warming Up: Responses to Cold

- Vasoconstriction: Blood vessels near your skin surface narrow, reducing blood flow and conserving core heat by minimizing heat loss through your skin.

- Piloerection (Goosebumps): Tiny muscles attached to your hair follicles contract, causing hairs to stand upright. In humans, this creates goosebumps—a remnant of our furry ancestors’ ability to trap insulating air in their fur.

- Shivering: Rapid, involuntary muscle contractions generate heat through metabolic activity. Shivering can increase your heat production by up to five times!

- Non-shivering Thermogenesis: Your body can generate heat without shivering through specialized brown adipose tissue and increased metabolism, particularly in response to cold exposure.

- Hormonal Adjustments: Thyroid hormone and adrenaline increase to boost your metabolic rate, generating more heat.

Behavioral Strategies in Thermoregulation

Beyond these automatic physiological responses, your conscious actions play a crucial role in temperature regulation—often as your first line of defense against temperature extremes.

Behavioral Cooling Strategies

- Seeking shade or air-conditioned environments

- Removing layers of clothing

- Reducing physical activity

- Increasing fluid intake to replace sweat losses

- Using fans or creating air movement

- Applying cold compresses to pulse points

Behavioral Warming Strategies

- Seeking shelter from cold environments

- Adding layers of clothing or blankets

- Increasing physical activity to generate heat

- Consuming warm foods and beverages

- Curling up to reduce surface area exposed to cold

- Social huddling (sharing body heat with others)

These behavioral adaptations complement your physiological responses and often work faster than the automatic mechanisms. Your hypothalamus coordinates many of these behaviors through motivation and comfort-seeking drives.

When Thermoregulation Fails

Despite its sophistication, your temperature regulation system can become overwhelmed or malfunction in certain situations.

Fever: A Reset Thermostat

During infections, your immune system releases chemicals that temporarily reset your hypothalamic thermostat to a higher temperature. This creates a fever—your body intentionally raising its temperature to fight pathogens. During a fever:

- Your “setpoint” temperature increases

- Your body initiates heat-conservation and heat-production mechanisms

- You feel cold and shiver despite having a high temperature

- Once the infection subsides, your setpoint returns to normal, triggering sweating to bring your temperature down

Heat-Related Illnesses

When heat gain exceeds your body’s cooling capacity, you can develop heat-related illnesses:

- Heat Exhaustion: Characterized by heavy sweating, weakness, dizziness, and nausea as your body struggles to cool itself

- Heatstroke: A life-threatening condition where your core temperature rises above 40°C (104°F), often with confusion, organ damage, and failure of the sweating mechanism

High humidity particularly challenges thermoregulation because it reduces the effectiveness of sweating—your primary cooling mechanism.

Hypothermia

When your body loses heat faster than it can produce it, your core temperature falls dangerously low (below 35°C or 95°F). This condition:

- Slows metabolic processes

- Impairs nervous system function, causing confusion and poor coordination

- Can lead to cardiac problems and ultimately death if untreated

Vulnerable Populations

Certain groups have less robust thermoregulation:

- Infants and young children: Have a higher surface area-to-volume ratio and less developed regulatory systems

- Older adults: Often have reduced sweat gland function and blunted perception of temperature extremes

- Those with chronic illnesses: Conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and neurological disorders can impair normal temperature regulation

- Individuals taking certain medications: Some drugs affect sweating, blood flow, or metabolic rate

Conclusion: Keeping the Balance

Your body’s temperature regulation system represents one of nature’s most elegant examples of homeostasis—the maintenance of stable internal conditions despite changing external environments. From the sophisticated sensor network to the central processing in your hypothalamus to the diverse effector responses, this system works tirelessly to keep you functioning at your physiological best.

Understanding how your body regulates temperature not only satisfies scientific curiosity but also provides practical knowledge for maintaining health in various environmental conditions. By supporting your natural thermoregulatory mechanisms—staying hydrated, dressing appropriately, and being mindful of environmental extremes—you help this remarkable system do its vital work.

The next time you shiver on a cold morning or feel sweat beading on your forehead during exercise, take a moment to appreciate the complex orchestra of responses working to maintain your perfect internal temperature—your body’s invisible but essential thermostat.